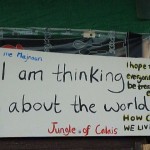

Yesterday I made my sixth visit to the refugee camp known as “The Jungle” in Calais. Usually I write about the people I've met or the stories I've heard: tales of horrors overcome, regimes escaped, hopes and dreams of new lives in the UK or France. Often it takes me a while to process what I've experienced enough to be able to write about it, but I get there in the end. And today is no exception but there are no happy stories here today; there is no hope. The Jungle is becoming a wasteland, a hell on earth, a place so desperate that even the best efforts of people like us to help seem to be futile.

Before we ventured into the camp we took a van full of clothes, shoes, tents and bedding to the new Care4Calais warehouse. Together we helped unload the van and put everything in its rightful place. When we tried to deliver shoes to another warehouse a fortnight ago we were told they had a backlog and weren't accepting any donations, which was pretty disheartening. However, this new warehouse seems like a slick operation and it was good to be able to leave plenty of stuff safe in the knowledge that it will soon be in the camp where it's most needed. Hopefully they'll get plenty of help to ensure there isn't a backlog there too.

Once we'd unloaded we set off for the camp, going in via the back entrance with the intention of delivering food parcels. Two weeks ago I'd been shocked at how much the camp had been devastated by the worsening weather, so I was fully prepared for that this time. The roads are even muddier and in places huge pools of water have collected, meaning your choice is either to wade through ankle deep water deep or to slip and slide your way around the muddy banks. I was wearing fairly watertight boots and went for the easier path. But many other people, in nothing more than flip flops or too-small shoes, were clambering around the edges. There's lots of mud everywhere and most paths are difficult to traverse. The are still lots of damaged tents, tents flapping in the wind, abandoned tents, but there's also much more building of temporary structures going on, including several huts in the area near the church where a fire wiped out fifty tents last week. Volunteers are also taking pallets in to give to those people still in tents, in the hope that raising them off the ground will help.

However, my resolve not to get emotional this time disappeared when we saw a man being carried by his friends, agony visible on his face. I don't know what had happened, whether he was ill or injured, but it was a harrowing sight to see someone in so much pain in a place where medical attention is basic, at the least. Later Dan came across a guy with a broken wrist; he was determined to get him some help and devastated when the medical centre was unattended.

The running theme of this visit was mostly about trying to find a safe place from which to distribute food parcels. We stopped initially by the church and a few individual food parcels were delivered to friends. However, a large crowd quickly drew around the vehicles and our calls of “No line, no line” were ignored. One man asked me for paracetamol and I eventually managed to find him some, but had to fight my way through the ten people trying to root through the boot of my car. Someone offered out a tin of sweets and the crowd grew even larger, grown men arguing about whether they had had one or two tiny chocolates.

Previously I'd taken bags of sorted goods and had struggled to make up mixed bags to take into the quieter parts of the camp. This time I'd deliberately mixed up the contents of each bag to make the task easier but there wasn't ever the opportunity to go for a walk, talk to people and offer whatever they needed. I tried to get individual bits and pieces from the car – a food bag for a family with nothing, a hat and scarf for a small girl – but every time I opened the boot the crowd pressed around and eventually I had to give up. I did, however, managed to pump up a football for a couple of guys who were adamant the muddy ground wouldn't deter them from a game.

We drove round to the front of the camp and parked up under the motorway bridge. We've left the cars here many times before, but this time a group of riot police came over to move us on. One tapped on my car window and said “Leave. Now.” I wasn't going to mess with him, so we drove back into the camp, turned left at the crossroads and parked up alongside some restaurants. One of our team did some distribution from the car window but it was a bad idea, and soon her car was surrounded by desperate people. The restaurant owner wasn't too happy about the crowd either, and banged at a car with a big stick, telling us to move away. We moved further along but by now the crowd was so big that there was no way we were able to get anything out to walk into the side paths.

We rejoined the rest of the team and the van and went to the back entrance, hoping to distribute out there where it was quieter. Again the riot police closed in on us, threatening to tear gas us if we didn't move away. We didn't resist. At one point some guy – I assume he was one of the long term volunteers, but I don't really know – came over to tell us if we weren't up to the job of distributing we should just go home and take our stuff with us. I pointed out that this was our sixth trip and we'd managed to self-distribute successfully every other time, except with the shoes – and we'd learnt our lesson there. I said we weren't novices, we knew what we were doing, but the situation was very different this time round. I'm sure he meant well, but it was difficult being criticised by someone simply because we wanted to help.

Eventually we decided to go right out of the camp and transfer everything from the cars to the van. Having only one vehicle was easier to manage and we parked near the church and were able to organise a single line and let a few people through at a time to the side door, where we gave them individual food bags. It was much more orderly and a couple of refugees helped out too. We probably had hundreds of pounds worth of food, but it didn't go nearly far enough, and when the food ran out there was still a huge queue of hungry people who had to go without.

One of my missions yesterday was to take a load of stuff over to “my” boy, Ridwan. Since I “adopted” him on our second visit there, he's moved into a “house” with six other Eritrean lads, and now I've become Mami to them all – so taking over provisions isn't quite as simple as it was initially. I had a huge holdall stuffed with coats, fleeces, tshirts, underwear and shoes, plus a rocket stove, wood and a big box of food. I saw Ridwan early on in the afternoon but then the challenge of doing the food distribution kept me busy for a few hours. However, eventually I was able, with the help of the rest of our team, to lug all the stuff over to his house and he and his friends seemed delighted to see us, delighted with the food and clothes … and even more delighted with the football I gave them, as a last minute gift! We stayed and chatted for a while, made plans to go over again before Christmas and take decorations for their house – of the six, four are Christian and two Muslim – talked about how I would help them when (never if, always when) they make it to England. “I'll call you Tuesday, from Swindon!” Abel told me. Another Eritrean guy I'd befriended had made it over to England in the back of a lorry on Saturday, though after a phone call and a few texts he's been incommunicado. I'm worried for his safety, but the fact that he made it there has revived the hopes of the rest of the guys. On the other hand, one of their housemates was missing – apparently he was arrested near the station and had been held by police for the last five days. At least he has a roof over his head and three meals a day, I joked… I'd taken food over for them a fortnight ago but that had run out and they'd only received one meal since, they told me. I left them a twenty euro note, encouraged them to eat at one of the restaurants that night, and hoped vainly that the provisions I'd left them would last a fortnight till my next trip.

After all the hassle of the distribution my spirits had been lifted by seeing Ridwan and his friends, but sadly our day was to have a sting in its tale. At some point a bag containing an iPad and some personal obsessions was stolen from the van, which was of course very upsetting for those involved. I guess over the last three months we've got to know some of the refugees pretty well; it's easy to forget that not everyone is so honest or trustworthy. For some people it would be easy for this experience to colour their view of the camp as a whole and make them less willing to want to help. After all, we have worked our butts off to make a difference here and for a while this felt like the ultimate betrayal. But of course one thief a community does not make. In every society on earth there are good and bad people, but we don't lose faith in the good because of the bad. Yes, people in the camp are desperate, and desperate times sometimes call for desperate measures, but the people we told about the theft were visibly shocked and I don't think this incident is any indication of the nature of the refugees as a whole.

There's a deepening sense of hopelessness and desperation in the camp. Many people came here not knowing the UK border is actually in France – they assumed the French authorities would be happy to let them leave and that it would be easy to get to the UK and apply for asylum here. Others were brought to France by people smugglers who took money to deliver people to the UK and then abandoned them in Calais. Yet more people didn't really know where they were going and followed others, only to end up stuck at the edge of France with no safe forward passage possible. Many people still try daily to jump onto the train or sneak into a lorry, but others have given up all hope of ever reaching England. Some have applied for asylum in France, only to be sent back to the Jungle while their application is processed. Others have been luckier – a Syrian family with two young children we'd befriended have now left their caravan in the camp and been moved to more suitable accommodation while they wait to see if they can stay in the country. But the look of despair is evident in the eyes of most people – they smile, they laugh, they thank you for your support but their eyes are always filled with sadness, hopelessness, desperation.

One of the questions I tend to ask people is why they want to come to the UK and the answers always fall into one of three categories – they want to study; they want to work; or they have family there. Not one person has ever mentioned benefits as a reason to come to the UK, and I must have talked to dozens of people if not more. Why not stay in France, I ask? They tell me the French people are hostile to them, they've heard work is hard to find (especially if you are black), education opportunities are not good, they don't know the language – after all, English is taught in every school around the world, more or less. As a country we've done a fantastic job of turning English into THE global language, of highlighting how welcoming and inclusive we are as a people, of turning “Britishness” into THE global culture – you only have to look at how well supported English football clubs are in Africa and the Middle East. So why are people so surprised when refugees escaping atrocities and war want to make Britian their home? Where would you go if you had to leave your homeland – a country with a hostile attitude and alien language and culture, or a country where you felt you would have a fair chance of integrating?

So I totally understand why so many people have got as far as Calais, but it's almost unbearable to see the horrendous conditions they are living in. It was pouring with rain at one point, there were gale force winds, and we saw people washing their feet at the cold water standpipe and then putting their socks and shoes back on. There's lots of illness – coughs, colds, scabies, flu and worse. Everyone is starting to look tired and depressed and malnourished. Kids scrabble around in the dirt, or are huddled up in inadequate coats, or stomping around in boots several sizes too large. Pregnant women receive no medical care; babies are living in damp caravans or leaky tents. I saw a blind man being accompanied around the camp by a friend, a man on crutches, others with bandages on facial wounds. How do you keep injuries clean when there are only four water pipes for 7000 people?

Last time I found it hard to hold back the tears. This time I kept it together in the camp but on the way home I had a good cry. I told my son that in some ways I wished I'd never gone to the camp in the first place. If I didn't know what it was like, I wouldn't have known, wouldn't have felt so upset, wouldn't have bonded with Ridwan and his friends. They wouldn't have known any different either. I said I didn't know how long I could keep doing this either, yet I feel I have to now, have to carry on, have to keep going. Dan pointed out that I've made a huge difference to the lives of so many people and I've done the right thing – and will continue to do so – and that I'm strong enough to carry on. He talks a lot of sense, does my son.

So yes, I'm feeling emotional again, but this time the overriding feeling is anger. I'm angry that fellow human beings have been forced out of their homes for whatever reason, only to end up in hell on earth. Angry that in the 21st century, in a developed, wealthy country and just 20 miles from Britain, there can be a third world worse than any developing country. Angry that the major charities have turned their back on Calais because it's not an “official” refugee camp. Angry that the police are making it as difficult as possible for volunteers to help. Angry that the French government don't seem to give a damn about what is going on on their soil. Angry that Britain claims to be a welcoming civilised nation yet the British government has spent millions of pounds on fences and security to keep out the people who most need our support. Angry that people can stand by and watch from afar as people suffer. Angry that so many people seem so hostile, both to the refugees themselves and the people who give up tiers time and money and energy to help them. Angry that the media is generally portraying this so negatively. Angry that a vast part of the UK population believes what they see in the media. But mostly just angry that this can be happening at all. Where has our humanity gone?

Was this on Sunday 28th November I ghink I saw you with the van with lots of people surrounding it

It was Sunday, yes. Eventually we did manage to do a safe distribution of lots of food, but it took a while to get to that stage.